When Work Ends and Leisure Takes Over

When Work Ends and Leisure Takes Over

Monday I returned from family holiday and based on a post by Martin Varsavsky, who linked the book Utopia for Realists by Rutger Bergman, I thought a bit about the end of work again, actually already read a lot of stuff around that subject.

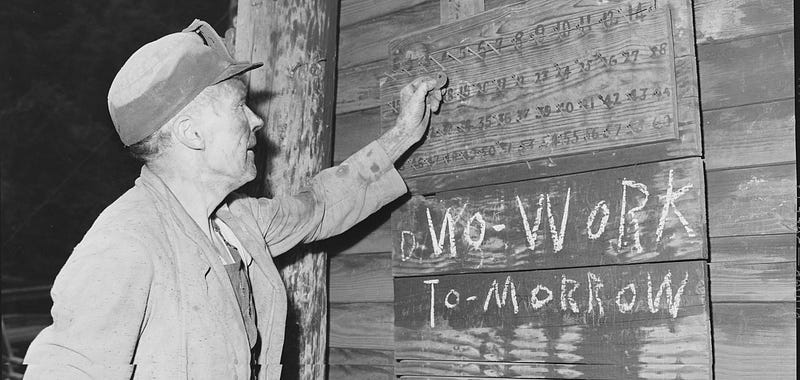

_Blaine Sergent, coal loader, putting up his check at end of day’s work.source._

I have to say that the book is good, but with a lot of standard deviation, alternating between very good and boring with some wtf moments in-between. What it does not lack is references and links to other things with lots of data, mixed with a bit of wit. See this part:

> Per capita income is now ten times what it was in 1850. The average Italian is fifteen times as wealthy as in 1880. And the global economy? It is now 250 times what it was before the Industrial Revolution — when nearly everyone, everywhere was still poor, hungry, dirty, afraid, stupid, sick, and ugly.

A lot of things have changed, yet we are going on in the same manner as years ago, even while “ _these days, there are more people suffering from obesity worldwide than from hunger_ ”. And Rutger himself is very clear in his words, but also supports himself by using quotes a lot:

> “The big reason poor people are poor is because they don’t have enough money,” notes economist Charles Kenny, “and it shouldn’t come as a huge surprise that giving them money is a great way to reduce that problem.”

So what about the homeless. Did you know that in most developed countries (I presume most, as he gives Europe and US as examples) there are more empty houses than homeless people? First cities have started given the homeless a place to live for free and found out that it is actually cheaper than not to do that, even without factoring in that those people suddenly start having a real life, a not to underestimate additional benefit of giving people the basis to live. This might seem counter intuitive, but remember Henry Ford?

He introduced the 5 day work week and everybody followed because it was a productivity boost. We need downtime. W.K. Kellogg moved to a six hour workday and found that his unit cost of production shrank, meaning he could pay the same as for an eight hour workday and accidents went down 41%. Tim O’Reilly wrote a good post call “To survive, the game of business needs to update its rules” with some common sense calculations and thoughts. The financial system is mostly serving itself and not the real economy and it finishes with a very good point:

> Here is one of the failed rules of today’s economy: humans are expendable. Their labor should be eliminated as a cost whenever possible. This will increase the profits of a business, and richly reward investors. These profits will trickle down to the rest of society. The evidence is in. This rule doesn’t work.

Rutger has some great data to make you think and extends that to e.g. the fact that universities might have helped us when we moved from 74% of all Americans being farmers to just 3%, because it taught many basic things, but with the new revolution that might just not be enough. And actually, the question is wrong. We should really, like Rutger says, not be asking what skills our kids will need in 2030, but rather which skills we want our kids to have. Where do we want this world to go. What is our new utopia?

I really believe in data but also in the narrative around it. This point here is very powerful for the immigration crisis:

> Take a Somalian toddler. She has a 20% probability of dying before reaching the age of five. Now compare: American frontline soldiers had a mortality rate of 6.7% in the Civil War, 1.8% in World War II, and 0.5% in the Vietnam War.30 Yet we won’t hesitate to send that Somalian toddler back if it turns out her mother isn’t a “real” refugee. Back to the Somalian child-mortality front.

So turning down refugees is wrong, period. Yes there are problems but we need to focus on enabling more good effects than preventing the few bad outcomes. Also if we move in a direction of universal basic income there might need to be rules like minimum taxes of X to be paid or other solutions to think about.

But the job market is not _a game of musical chairs_ , rather like women, immigrants create new jobs. But as I discussed with a few friends, the more socialist side of politics are just so amazingly bad at telling their story it is appalling. We seriously need to work on that, because often it is not only the better thing to do to unconditionally help the poor, but it also makes business sense. Even the bible knew:

> “Look in depth at Exodus 16,” he wrote, “the people of Israel in the long journey out of slavery, they received manna from heaven. But,” he continued, “it did not make them lazy; instead, it enabled them to be on the move…”

Instead we are controlling and forcing people. That might just be the wrong thing even if it partly feels right. And what if the jobs are going away anyway and we are not the first ones.

> By 2030, Keynes said, mankind would be confronted with the greatest challenge it had ever faced: what to do with a sea of spare time. Unless politicians make “disastrous mistakes” (austerity during an economic crisis, for instance), he anticipated that within a century the Western standard of living would have multiplied to at least four times that of 1930. The conclusion? In 2030, we’ll be working just fifteen hours a week.

So what if the jobs are not the solution but the problem, the title of an article by James Livingston. As he says:

> Shitty jobs for everyone won’t solve any social problems we now face.

What a great quote. :)

And there comes the question:

> And what would society and civilisation be like if we didn’t have to ‘earn’ a living — if leisure was not our choice but our lot?

And yes, the article goes deep into the our social connection to the idea of a job, what could follow, how to finance it, and a lot of other points connected to universal basic income. And if work really vanishes, that _impending end of work raises the most fundamental questions about what it means to be human_. He makes the problem very clear at the end:

> Can you imagine the moment when you’ve just met an attractive stranger at a party, or you’re online looking for someone, anyone, but you don’t ask: ‘So, what do you do?’

> We won’t have any answers until we acknowledge that work now means everything to us — and that hereafter it can’t.

What does all this mean for me? We will still need people and we will need to enable people to use their brains as freely as possible to solve the worlds problems. This really makes basic universal income something that is more or less inevitable and we will need to find a way to make this happen. We will need to be a socially responsible world but will need to use data and market forces to get there. And due to the fact that we are very likely moving into a direction of requiring less jobs to be filled, we will have to find other things to identify us in.

I am an eternal optimist though and think we can make it. The question is more how painful the way will be to get there.